Vikings and Kievan Rus

From the end of the VIII century until the middle of the XI century, Vikings were one of the most prominent forces in Europe. They left a lasting reputation as fierce warriors, skilled seafarers, and brave explorers that we still hear tales of today. However, both in popular culture and in Western scholarly research, more attention has been given to their exploits in Western Europe. Their relationships with the East have been discussed far less, so it is only natural that we would want to take a deeper look into the Viking's interactions with their largest South-Eastern neighbor: Kievan Russ.

We have to start by asking two important questions: who are the Vikings and what was Kievan Russ at that time?

So, who were the Vikings and where were they from?

Despite the popular answer about “northern warriors”, the word “Viking” originates from the Old North word “vika”: the distance between changes of oarsmen shifts in a long sea voyage, which became a metaphor for a long sea voyage itself. It was an occupation, often temporary, not an indicator of ethnicity or cultural belonging.

Western European sources associate Vikings with people originating from Scandinavia. However, Scandinavian sources also talking about Oeselian Vikings, for example, Estonians from the island of Saaremaa and Curonian (Lithuanian/Baltic Slavs) Vikings raiding Southern Sweden.

The same person in one circumstance could become a Viking or mercenary (having the appropriate skills), or to be a trader or bond (free farmer/landowner).

Were Slavs Viking too?

Baltic Slavs were definitely recognized as Vikings by Scandinavian records. But what about Eastern Slavs? Those who were participating in the Viking raids on the Byzantine Empire and across the Caspian Sea were technically “Vikings”, but neither Byzantine nor Arab sources were using that word. Instead, they used the word “Rus”.

Where did the word Rus come from and what does it mean?

Unlike the word “Viking”, the word Rus was a self-denominator for Northern traders, warriors, and mercenaries, who operated in the territory of future Kievan Rus.

The word Rus itself originates from the old name for Southern cost of Sweden – Ruotsi.

As early as 838, Byzantine sources mention a “Khaganate of Russ” (obviously, by analogy with the Khazar Khaganate) located to the South-East of the Baltic Sea.

Who was populating the territory of Kievan Rus?

The territory late becoming known as Kievan Rus in late VIII – early IX century had a mixed population consisting of several previous cycles of migration. The latest one was the migration of the Slavic people from the territory of today's South and Central Poland to the East. As they settled, they interacted with the population left behind from past migrations. For the purpose of this article, the most important were the people of Gothic origin – remnants from the Ostrogoth kingdom of the II – V centuries.

(Indeed, archaeology supports Northern legends saying that ancestors of the Scandinavian population migrated there from the territory of today's Ukraine, or, at least, there was some sort of ethnic continuity between Eastern Europe and Scandinavia during late Roman period).

However, the population of the forested zone – especially of upper Volga basin and to the East still was predominantly finno-ugric, and remained this way until around the XVI century.

Why did the Vikings have to travel East?

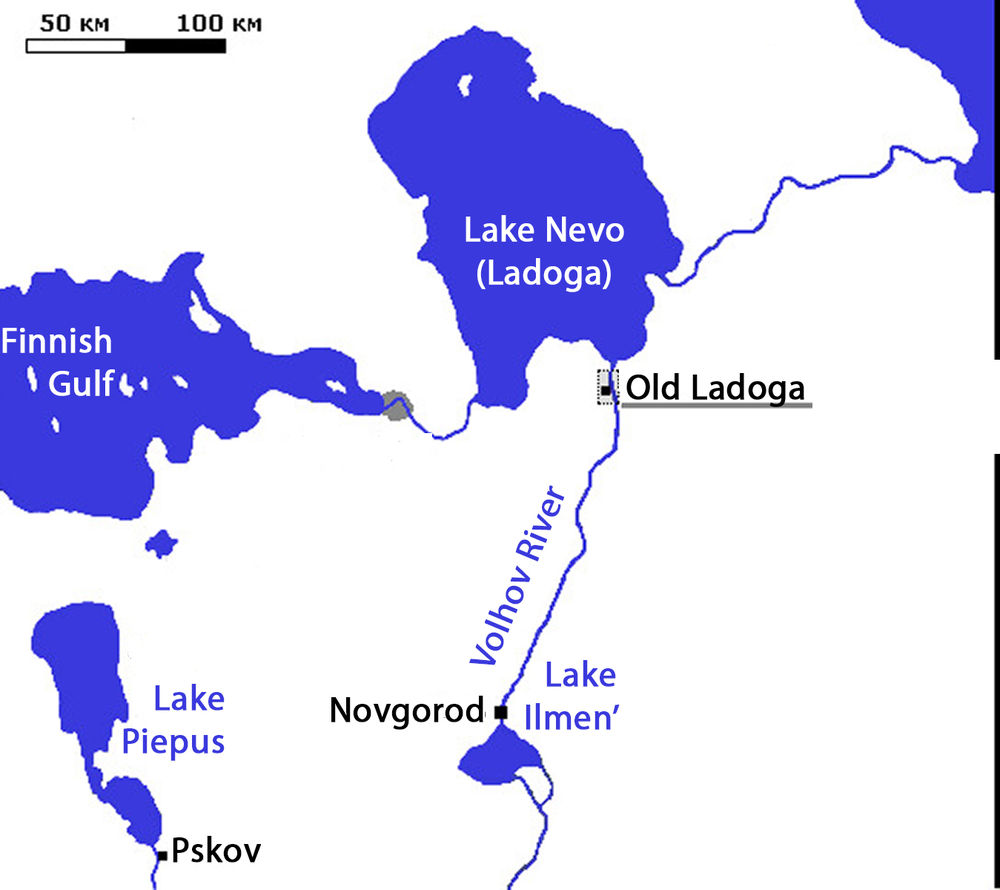

Military raids of the coastal areas of Western Europe were one of the many ways the Northern contingent was securing the profit. Trading with the Caliphate and Byzantine Empire was, perhaps, a even more important source of revenue. The oldest Scandinavian trade outpost we know about was established in Staraya Ladoga (or Aldeigjuborg in Old North ) in 753. This was 40 years prior to the infamous raid on Lindisfarne monastery, which is considered “the official” beginning of the "Viking Age" in Western European history. The fact that this outpost was established before the start of the "Viking Age" proves how incredibly vital this source income was.

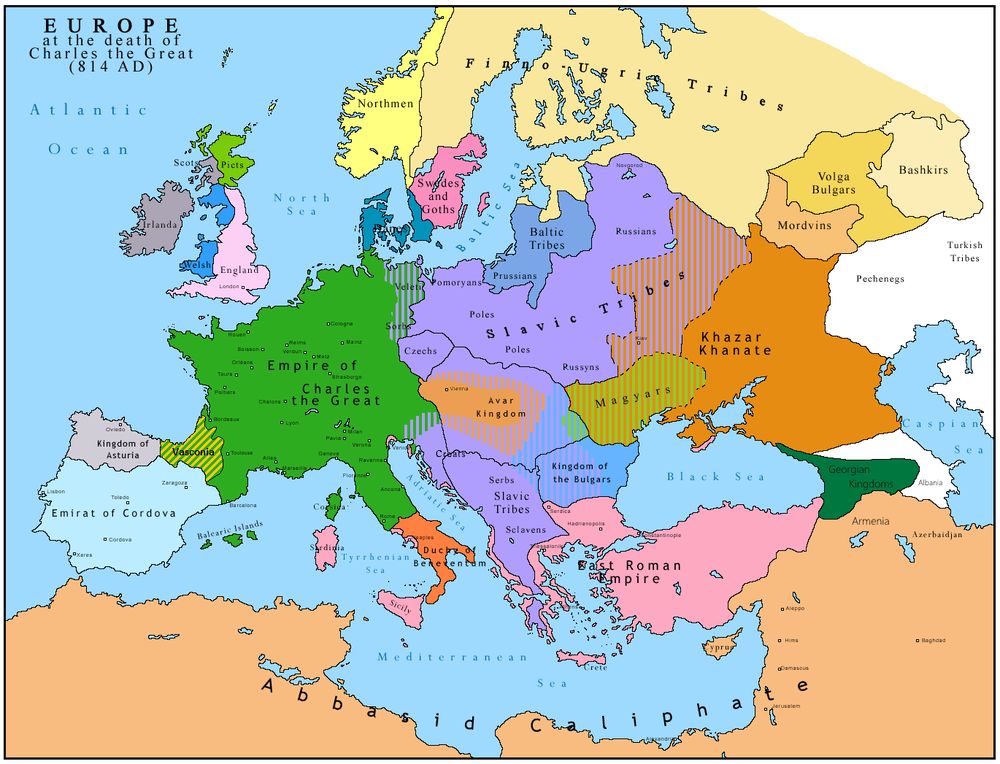

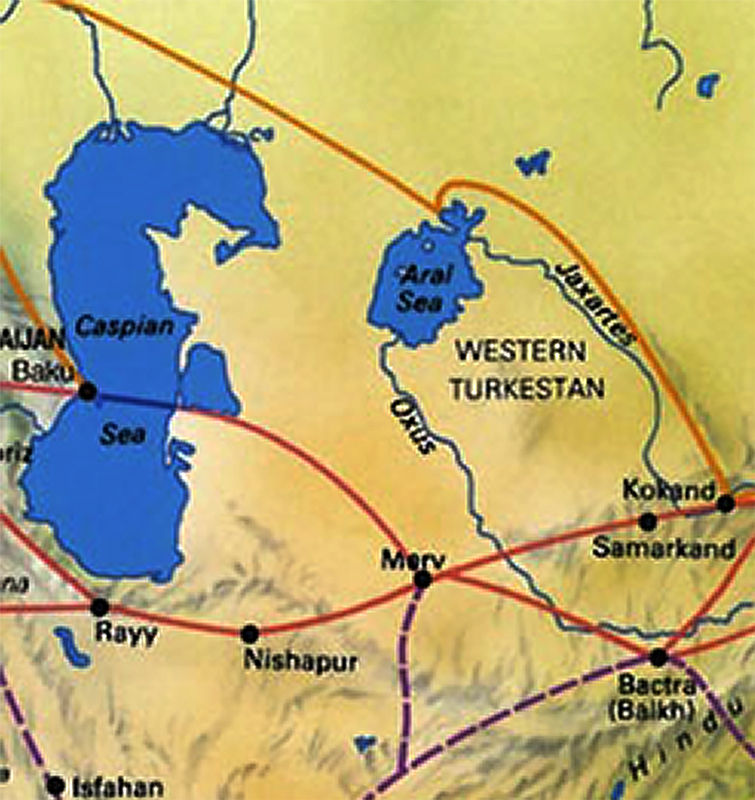

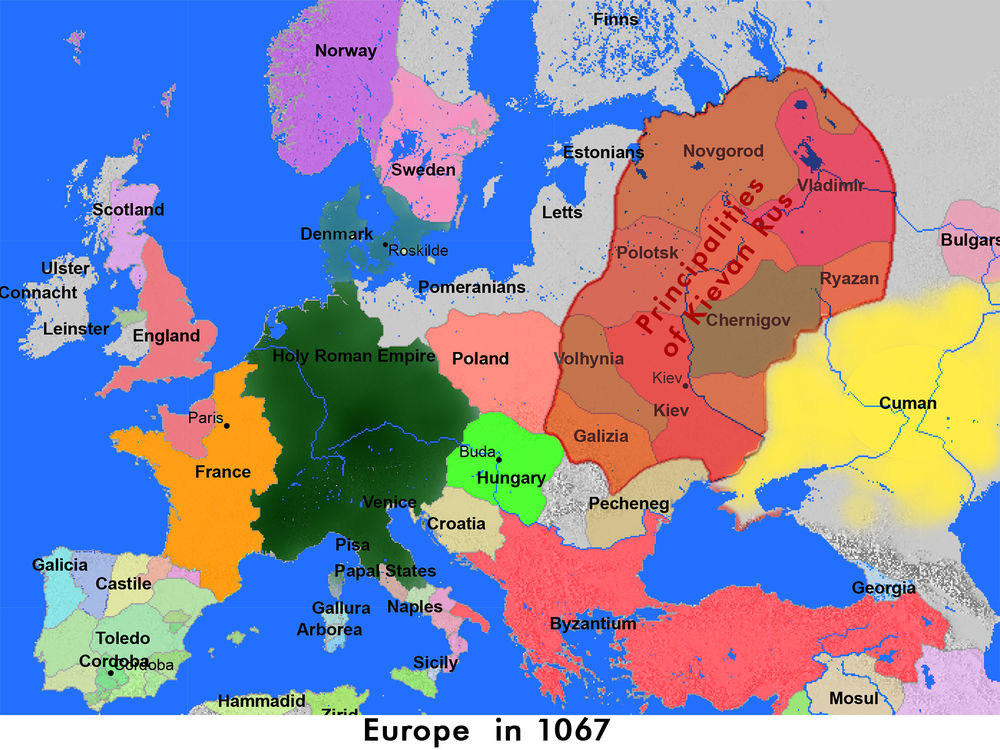

If we looked at the map of Eurasia in the IX century, we would see that the “North route” of the Great Silk Way was controlled by the great trade cities of Transoxiana (meaning “beyond Oxus” – today the Amu-Daria river) and various Turkic confederations East of the Volga river, with the Khazar Khanate to the West of it. The middle part of the Volga basin was controlled by Volga Bulgar. The “South route” was controlled by the Arab Caliphate from the Hindu Kush to Asia Minor, effectively cutting out the Byzantine Empire from direct access to it.

To secure trade with the Silk Road and Caliphate, Scandinavian traders needed to secure a route from the Eastern Baltic coast through the river system of Neva, Volhov and the upper Volga, to the Caspian sea. To get access to Byzantine trade they had to travel through Vistula and Dnieper to the North of the Black Sea to the Byzantine outposts of Cherson, Chersones, and Kaffa.

Amber, pelts, and slaves were traveling South on this “Road from the Varangians to the Greeks”, as it was called later, and silk, spice, and fine armor were traveling North.

Slavic-Viking relations

Unfortunately, we don't have any reliable records that tell us about the earliest stages of the relations between the confederations of Slavic tribes and bands of Vikings (and later – merchants) traveling to the South and East. The earliest Kievan Rus chronicles provide legendary accounts suggest some initial conflicts – perhaps sometime in the first half of the VIII century.

However, in the middle of the VIII century (as we mentioned above), Vikings had already established a permanent trade outpost at the Old Ladoga and started the process of settlement in that area.

We may be observing the same pattern as in Western Europe: initial raids, the establishment of the permanent settlements, creating of proto-states, like in Normandy, Northern England, and Ireland, only more than a century earlier.

Rurik and other Vikings in Rus

To the great dismay of some current Russian “patriots”, from both historical accounts and archaeological data, it seems that Viking bands and Scandinavian settlers played a very significant role in the creation of the Kievan Rus.

In the period between the second half of the VIII century and the early IX century, we can observe a steady spread of Scandinavian artifacts from the Old Ladoga region, to the South.

More historical records appear in the mid-IX century when Rurik (that is Slavic version of his name, which was, probably Hrøríkʀ; c. 830 – 879) proclaimed the city of Novgorod, which grew-up around Scandinavian fortifications on the South shore of Ilmen Lake, to be a capital of his domain in 862. At that time, Novgorod (Holmgard or Nygardr in North Sagas) was already an important center of the trade between Scandinavia, Volga Bulgar, and Constantinople and at moving administrative functions to it from Old Ladoga seemed very reasonable.

Rurik wasn't the only one of Nothern konungs who was looking to establish a permanent domain in Eastern Europe. The sons and grand-sons of the Ragnar Lodbrog in 830 established control over the Kyiv region, the key city for controlling the trade with the Black Sea region over Dnieper River. Ragnar's grand-son Haskuld (Askold in Slavic tradition) gathered enough forces to conduct a surprise raid on Constantinople itself in June of 860. The Byzantine fleet was tied up in the war with Caliphate, and Haskuld besieged Constantinople for 2 months.

While Byzantine tradition claims that Michael III successfully fended off the attack by August 4, contemporary historians believe that the more likely scenario is that Russ forces were just paid off (as often happen in Western Europe). Indeed, letters of Pope Nicolas I to Emperor Michael III support exactly that view.

Byzantine historian Photius claims that Russ had at least 200 ships. Going by the design of Scandinavian warships of the period, that gives us a number of about 10-12 thousand soldiers. Even taking into account Byzantine fondness for exaggeration, it is highly unlikely that all of these people were of direct Scandinavian origin. It seems that in the mid-IX century, Swedish in origin elite were intensely recruiting Slavic and Baltic soldiers to create a foundation for the Slavic-Scandinavian substrate of future Kievan Russ. It seems even more plausible, that Haskuld in Kiev also invited forces from Novgorod and Old Ladoga to join him in the successful raid. It is also obvious that his military success created a lot of envy among Rurik and his closest retinue.

The Creation of Kievan Rus

In mid-860 to 870, Scandinavians in Kyiv were controlling the routes to the Black Sea, and the Scandinavians in Novgorod were controlling the routes to Volga Bulgar and the Caspian Sea. However, Rurik died in 879 leaving his seat of power to underage son Igor – and his close relative Oleg became the regent of the young prince. In 880-882, Oleg staged a successful military campaign taking over Smolensk and Lubech and - through a deception - killed Haskuld and overtook Kyiv. He immediately proclaimed the unification of the land between Kyiv and Novgorod under the rule of Kyiv, thus, consolidating the trade routes under one hand. He also started methodically pushing Khazar Khanate out from the trade business with the Byzantine – as well as from collecting tributes from Eastern Slavic lands.

Oleg ruled more or less successfully over the newly unified Kievan Rus for the next 30 years, gaining the epithets “Wise” and “Prophetic” in later official chronicles. However, an apparent lack of legitimacy of his later dynasty – as well as lack of spectacular military success on the Byzantine front during his reign – led to the fabrication of the story of his successful raid on Constantinople in 907, embellished by all kind of fairy tales. Byzantine sources are spectacularly silent of any such raid at all.

In reality, Oleg successfully developed a trade relationship with Constantinople through a combination of intimidation and small skirmishes immediately counterbalanced by offering peace agreements and military help from mercenaries. Indeed, two major trade agreement between Rus and Constantinople signed in 907 and 911 looked very favorable for Kiyv.

Relations of Kievan Rus and Byzantine Empire

After the successful raid of 860, Constantinople not only acknowledged the existence of the “Slavic-Scandinavian problem”, but took significant diplomatic and cultural efforts to resolve it, dispatching numerous missionaries (with brothers Cyril and Methodius being the most famous among them). Their goal was to convert Slavic tribes to Christianity, give them the Greek-related alphabet and bring them into the fold of Byzantine culture. Constantinople also started actively recruiting Rus soldiers as special mercenaries (since 874) to protect the Greek coast from other Vikings arriving in the Mediterranian from the West and from Arab naval raids. The best way to beat Vikings is to hire them!

At first, that strategy was not looking very promising, but in the long run, it proved to be very successful. More and more Khagans of Rus had to rely on the Slavic recruits for his war bands – and more and more Greek Christianity were penetrating the cultural landscape of Kievan Rus. While Igor, who succeeded Oleg in 913 was still a pagan, his wife Olga [Helga] was already a devoted Christian.

Military successes and failures of Kievan Rus in the X century

Concerned about increasing Byzantine influence on the North Shore of the Black Sea, in 941 Igor organized a massive military campaign against The Byzantines, relying mostly on Slavic and Pecheneg troops, which led to more or less disastrous results. This time the Byzantine navy was prepared – and annihilated Igor's ships with “Greek Fire”, while the Byzantine land army crushed Igor's landed forces. Igor had to run, leaving plenty of his allies captured by the Byzantine army. That encounter with Constantinople is especially interesting for us, because, for his revenge, Igor tried to organize a second campaign in 943 by calling to Swedish relatives of his wife for more Northern troops. The pattern of calling reinforcement from Scandinavia, either for the external campaign or for internal civil conflicts, continues in Kievan Rus through the mid-XI century. There are plenty of references for such events in the Nordic Sagas, and they, sometimes, shed unexpected light on rather murky aspects of Kievan succession and internal struggle.

Igor's second campaign had mixed results: Kyiv was forced to sign a new trade agreement with Constantinople under much less favorable terms, monetary gain from the campaign was less than expected, while expenses for hiring the best Nordic Vikings were very high. In 945 Igor was killed in an attempt to collect extra taxes from his Slavic subjects and was succeeded by his son Sviatoslav. Note, that Sviatoslav's name was already Slavic, while still non-Christian.

While having Slavic name, Sviatoslav still looks more like a character from Nordic Saga. He tried to be a perfect warrior Konung, putting his military band above everyone else and re-establishing Nordic religious ceremonies in the way adapted for his increasingly Slavic subjects. (It is believed by scholars that traditional Slavic beliefs were earlier derived from common Proto-Germanic roots, so, Thor and Perun/Percunas had more in common). Using unfavorable weather for the Khazar Khanate, and gaining support from Pecheneg nomadic tribes, Sviatoslav achieved military dominance over the Southern Stepps. However, when he tried to extend his success into Byzantine territory, it proved to be fatal. His army was defeated by the Byzantines - his Pecheneg allies betrayed him – and he was killed in 972.

Vladimir the Great, the acceptance of Christianity and alliance with Constantinople

Sviatoslav's son Vladimir turned out to be a much more shrewd political leader. After an initial failure in the struggle for power with his brother Yaropolk, Vladimir fled to Norway to his relative Haakon Sigurdsson (then ruler of Norway) – most probably through his grandmother Olga of Kiyv (who was from prominent Viking family lived in Pskov). There, he gathered a Viking army and successfully return to power in 978. He continued a campaign of skirmishes, negotiation, and intimidation against the Black Sea territory of Byzantine, but in 987 he seized the opportunity of a lifetime: the Byzantine Emperor Basil II was desperately trying to resist the rebellion of Bardas Phocas, who declared himself a new Emperor.

Vladimir offered Basil II the help of his 6000-strong veteran army in exchange for exclusive trade preferences, recognition of the Kyiv state as a Byzantine equal ally, and marriage to the Emperor's sister Anna. For all that, well, he had to accept Christianity. But for Vladimir, who already experimented with all kinds of religions from Judaism to the new syncretic religion of his own invention, that was a small price. In 986, after the victory, Vladimir took the Christian name of Basil (as a courtesy to the Emperor) and proclaimed himself the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus and Christianity – an official religion. In turn, in 988 Basil II established the famous Varangian Guard, recruited from both Scandinavian and Rus warriors – and, until 1066, it stayed predominantly Russo-Scandinavian.

Relations between Kievan Rus and Scandinavia in XI century

The change of religion and even bloody baptism of Novgorod and Pskov did not undermine relationships between Rus and Scandinavia: Scandinavia itself was in the process of accepting Christianity (with its' own bloody excesses), and a tradition of mutual military help, intermarriage and providing refuge in case of internal conflicts continued until 1054. Vladimir's son Yaroslav the Wise was married to Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden (daughter of Olof Skötkonung, King of Sweden), and Yaroslav's daughter Elisif (Elisabeth) was married to King Harald Hardrada of Norway. Olaf II Haraldsson of Norway took refuge in Kyiv in 1028 after his initial unsuccessful introduction of Christianity to Norway. It was Yaroslav who helped him gather the forces for his doomed attempt to regain the Norwegian crown in 1030. And before that, in 1015-1019, Yaroslav successfully used Viking troops to defeat the coalition of his brother Sviatopolk and Polish king Boleslaw (Eymund Saga).

Archaeological findings very much support this picture of initially very close relations slowly and gradually drifting apart. If we look at Novgorod jewelry (because Novgorod and Pskov had historically closest relations with Scandinavia), the earliest examples in IX and X centuries are predominantly Viking or Viking-styled.

Jewelry of the XI and XII centuries gained more local and Iranian motifs, while stylistically it is still related to North.

Earrings also became more and more popular in Kievan Rus, while still absent in Scandinavia where traditional temple rings were preferred.

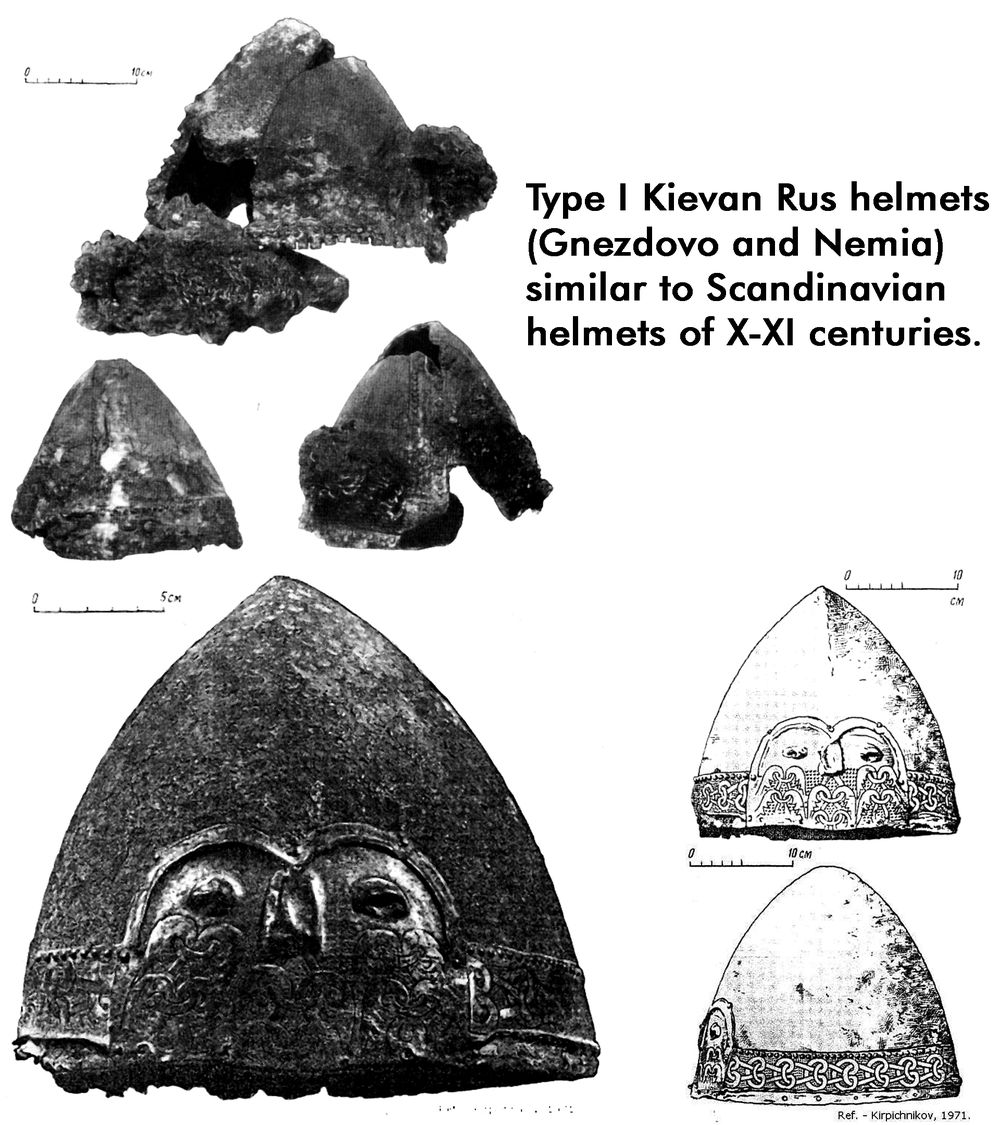

Kievan Rus helmets

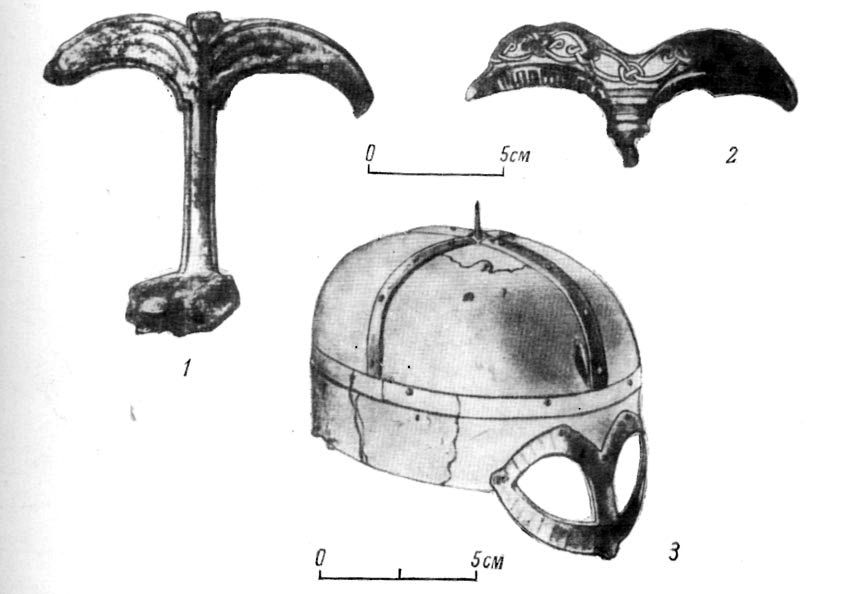

In the earliest stages, we have an armament complex of Rus which is predominantly Viking. Early examples of helmet fragments from the IX and X century found in Novgorod also belong to distinctive Gjermundbu types of Viking helmets.

Later helmets from the X century are also of the distinctive conical type used everywhere in the North.

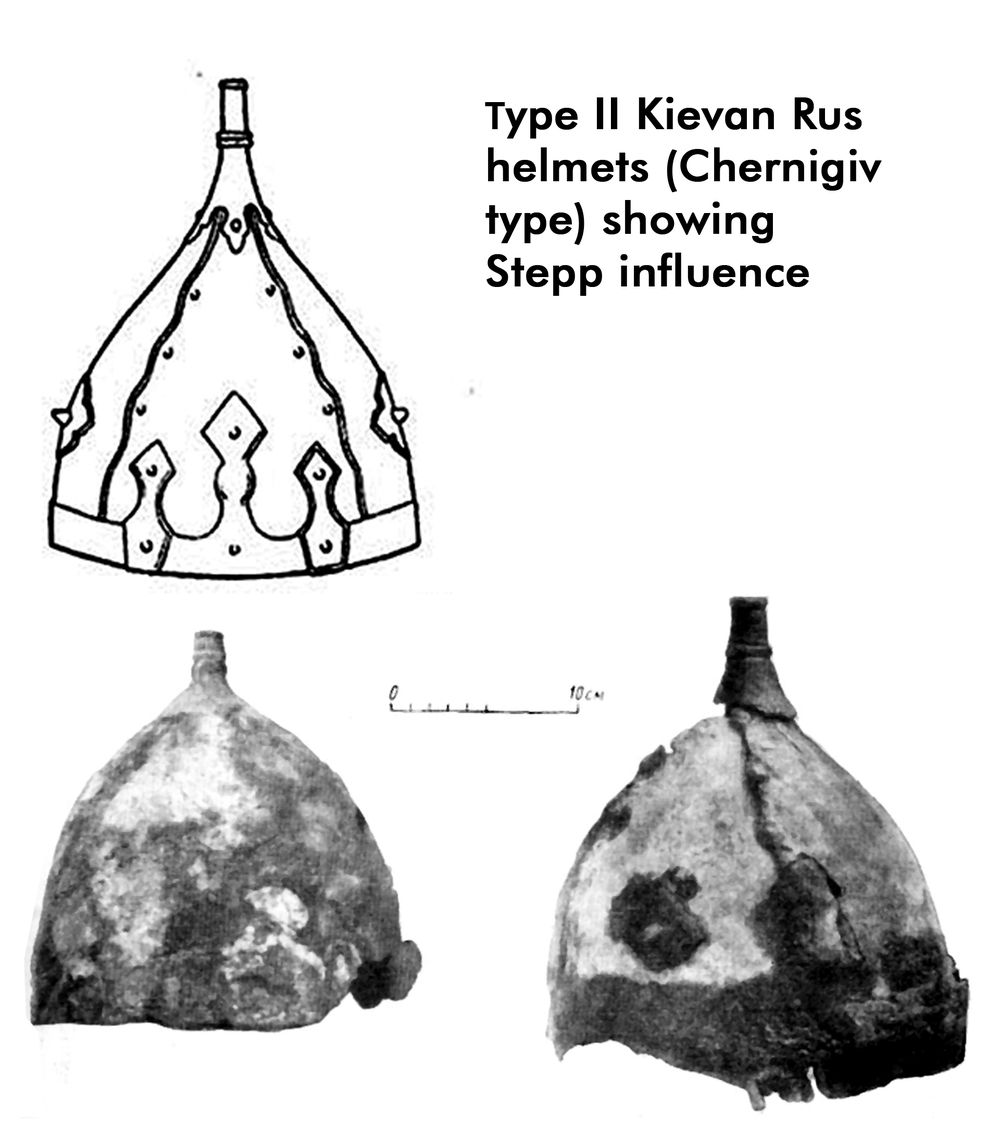

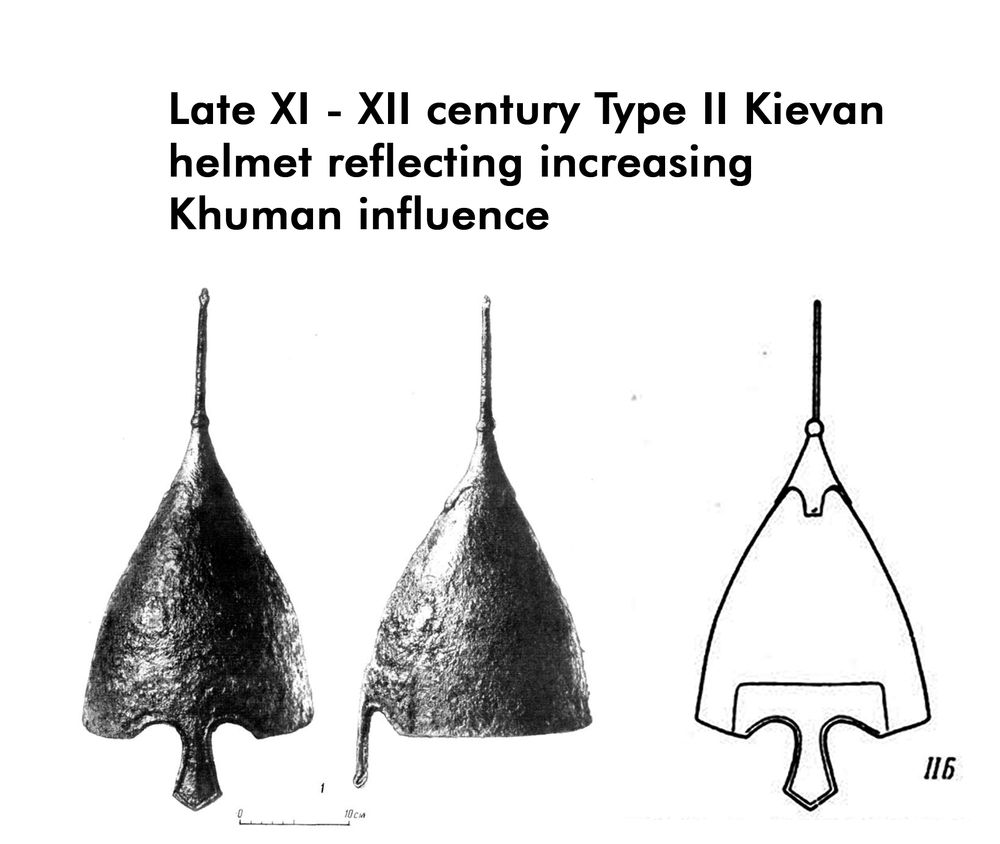

However, as early as the late X century, we are starting to see helmets more and more related to Central Asia tradition – and used by Khazars, Pecheneg, and Khumans.

From the middle of the XI century onwards, helmets in Kievan Rus became predominantly of types associated with Pechenegs and Khumans.

Kievan Rus armor

Until the intense military conflicts with the Byzantine Empire and Great Steppe nomads, we see some fragments of chainmail. Use of leather armor is highly probable, but leather decays even in the over-saturated soil of Novgorod (where we do have plenty of leather survived from XII and XIII centuries), so we had to be extremely lucky to find elements of leather armor from the IX and X centuries.

We do have more evidence from later in the X and XI centuries, both in iconography and archaeological findings. In that period, Kievan Rus begins rapidly adopting scale and early lamellar armor from Byzantine. With the increased importance of cavalry, we also see a transition from the round shield to “kite”-shield (as Normans did at the same time).

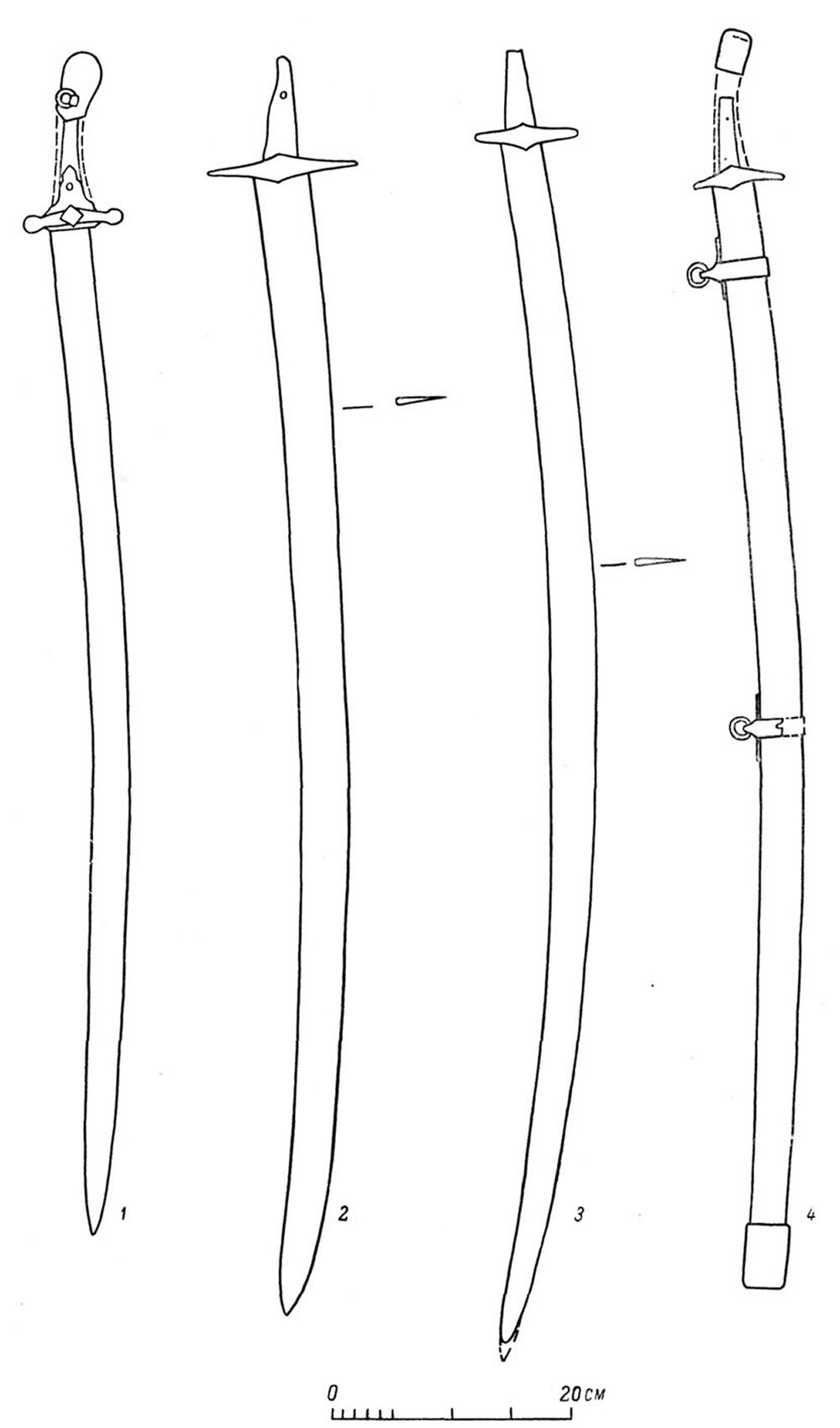

Swords of Kievan Rus

Are Slavic swords Viking?

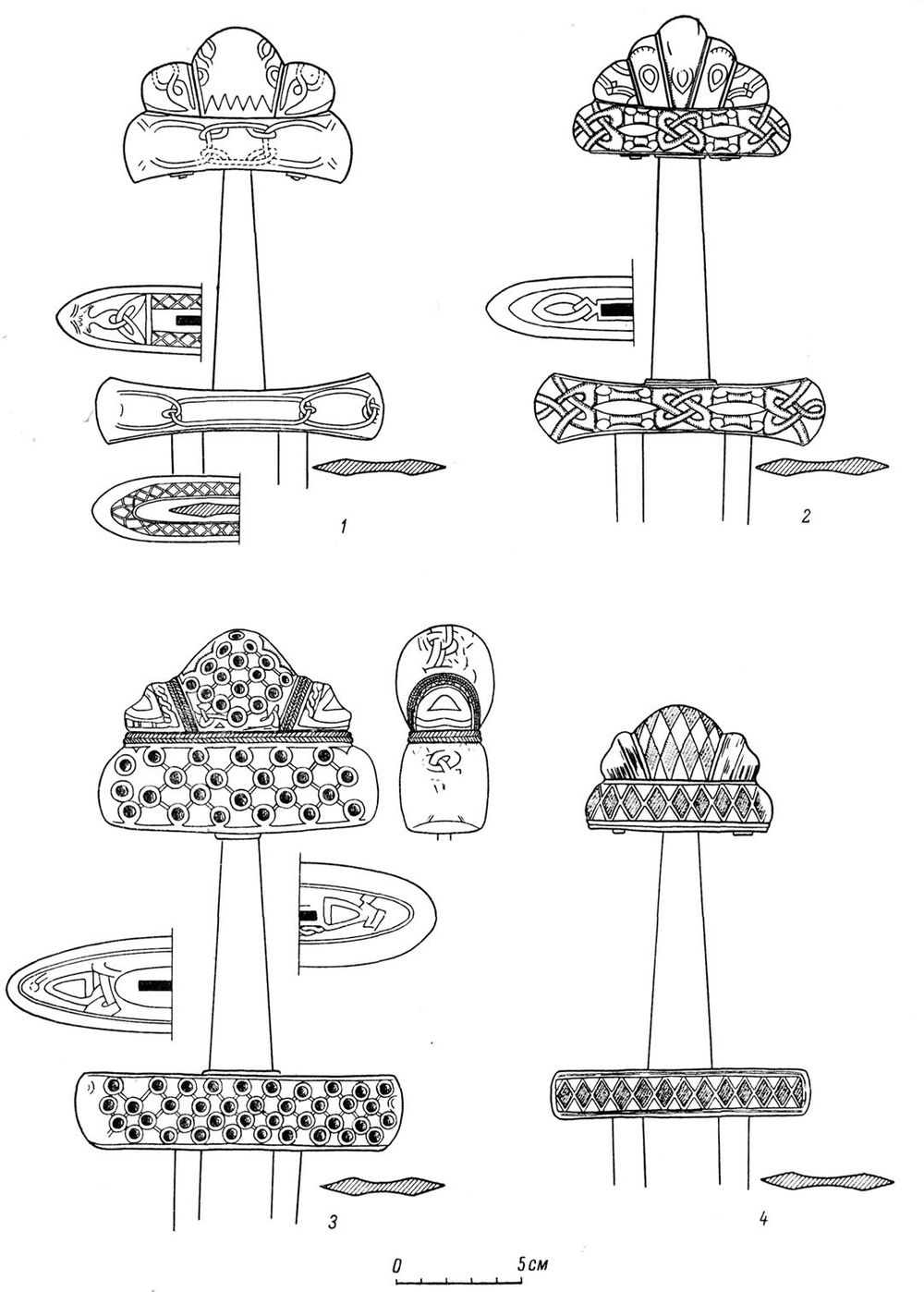

Even more telling is the evolution of the swords found on the territory of Kievan Rus.

Yes, indeed, early “Slavic” swords are Viking swords. Even more important, in the period between IX and XII centuries there is very little evidence of any significant blade manufacturing in Kievan Rus, and ALL blades were imported there. In IX and X centuries Scandinavia was the only source of blade import and we see Viking swords of familiar Petersen types, later examples getting guards decorated in more local fashion.

|

|

But in the late X – early XI century, Kievan Rus warfare deviated more and more from that traditionally associated with Vikings: Kievan princes were having to deal with Pecheneg and Khuman cavalry, and more emphasis was put on the development of their own cavalry. Comparatively, the North traditionally emphasized naval warfare and foot soldiers for land operations. That's where we staring to see original functional modifications of the cross-guard and pommel of the swords to adapt them to the horseback fighting while retaining some traditional Nordic decorum – and, always, the Scandinavian blade. Swords with the handles of that type are not found in Scandinavia at all.

Starting from the XI century we see also a widening use of sabers – imported through Khumans from Central Asia and Trans-Oxiana. From the XII century, the whole complex of armament for the Kievan Rus warrior started to look increasingly similar to their Stepp counterparts.

Conclusion

There were several reasons for Rus and Scandinavia drifting apart.

First, Great Schism between Rome and Constantinople in 1054 (Scandinavia became Catholic and Rus – Orthodox) definitely played a huge part. Second, both Scandinavia and Rus entered a period of internal political conflicts in the process of establishing conventional Medieval more or less centralized states. Intense infighting in Scandinavia, conducted by necessity through naval warfare, led to rapid deforestation of Southern Scandinavia, leaving it without timber suitable for traditional Viking ships. Loss of control over Northern England and Ireland also left Scandinavia without their traditional source of oak. The coastal cities of the Southern Baltic picked-up the trade functions leaving Scandinavia without a significant portion of their revenue (Due to a different technology of ship-building, they had a wider choice for timber). As a Christian state, Kievan Rus also had the option to look for trade and military support increasingly from their closest neighbors – Poland, Hungary, and Khumans – while relying on Byzantine in questions of religion, architecture and “high culture”.

The Age of Vikings ended with the death of Harald Hardrada a Stamford bridge in 1066. Kievan Rus was already culturally drifting away from Scandinavia, however, old ties with the Northern traditions were still strong in Novgorod, which established itself as an important center of Baltic trade. Judging by the archaeological findings and genetic analysis, Novgorod, perhaps, played as a refuge for some conservative Scandinavian elements, who were not fully content with Christianity. The West-Eastern territories of Novgorod were completely out of reach for Kyiv, and we see a lot of jewelry reflecting BOTH Nordic and Christian symbols. These artifacts we are continually observing as late as the XII century. Also, current genetic analysis Y-haplogroups of the Pomorian population (South cost of White See) showed their close relations with the Medieval population of Southern Sweden.

Intense contacts between Sweden, Denmark and Novgorod resumed in late XII-XIII centuries when now unified states – the Kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark and the Republic of Novgorod – begin competing for the colonial territories in Finland and today Estonia and Latvia.

Write a comment

Please log in or sign up to post comments without moderation